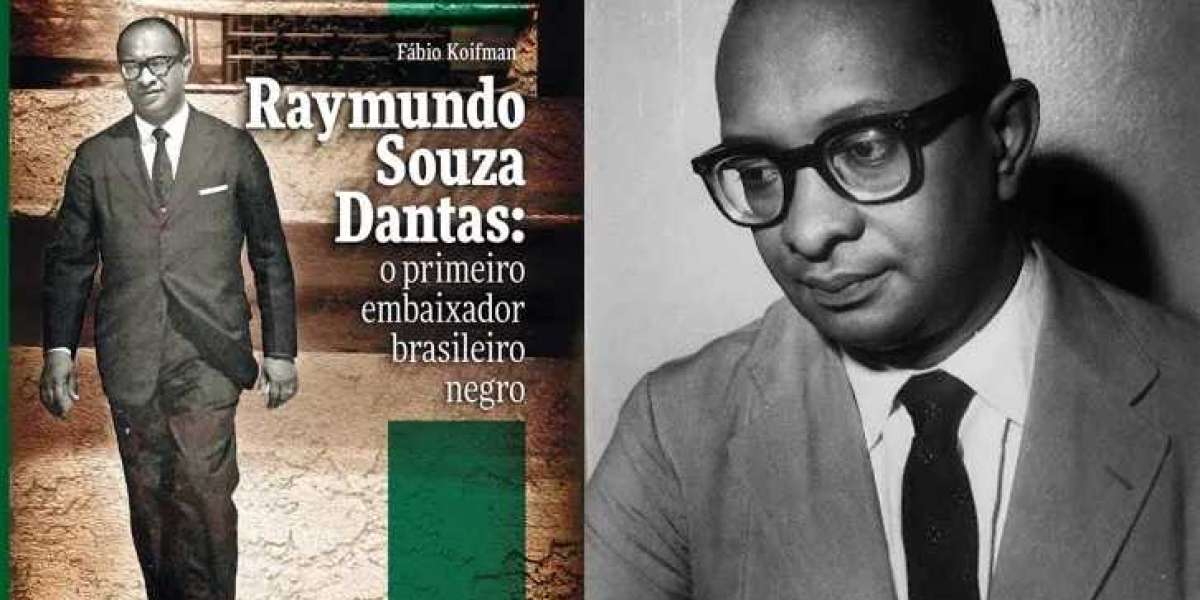

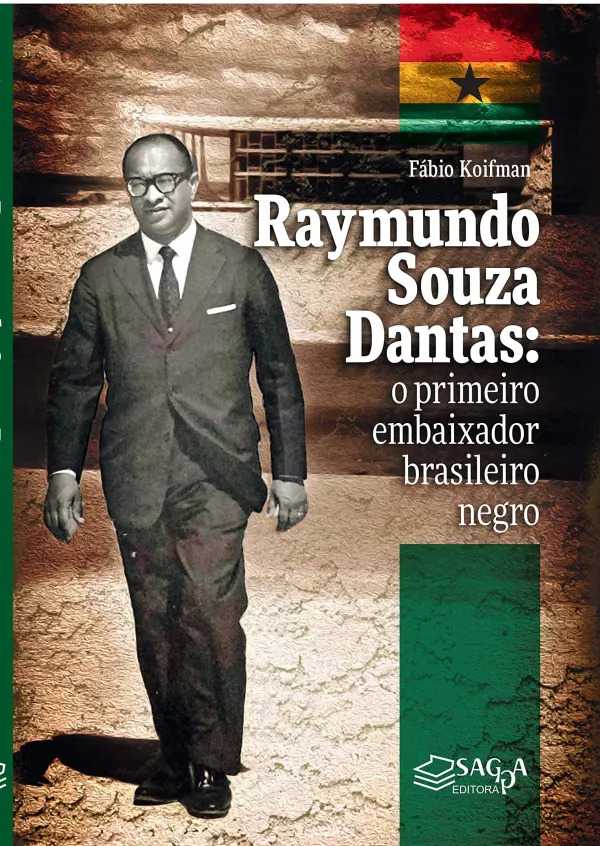

New biography sheds light on the life of Brazil’s first black ambassador, Raymundo Souza Dantas, and exposes deep-seated racism in Brazilian diplomacy

By Marques Travae of https://blackbraziltoday.com/

Back in the early 2000s, when I first got into the ‘’Brazil thing’’, I remember coming across the news that the country’s first black ambassador had died. I knew that anything having to doing ‘’the first black’’ anything was an important story, but even as I had only been exploring the internet for a few years at that point, I remember not finding much information about him at the time.

Of course, in those early years, there were only a handful of blogs and websites that dealt with specific stories relating to black Brazilians, so, for the most part, if it wasn’t on a large website, you just didn’t hear much about it. With all of the Afro-Brazilians websites, social network groups YouTube channels, etc. these days, there is a lot more focus on this parcel of the population and the due to this presence, the mainstream media has been forced to pay more attention to stories that are important to this community.

Anyway, to answer my own question, the reason that I didn’t hear much noise about the death of the country’s first black ambassador was the very same reason that a large percentage of the black Brazilian population itself wasn’t very familiar with important black Brazilian personalities: Brazil’s media and history books simply ignored them. These days, the black community itself is demanding and often doing the research on these figures themselves, which in turn seems to be influencing mainstream outlets to also give more space to these stories.

In this case, the person whose life has been uncovered more in depth is Raymundo Souza Dantas (1923-2002), a writer from Brazil’s northeast. A man of humble origins, he became first black man chosen to be an ambassador in the country’s diplomatic ranks, even as his presence was opposed by a racist, white elite.

Dantas (1923-2002) was named Brazil’s ambassador to Ghana by then-President Jânio Quadros in 1961. His appointment at the time was greeted positively by progressive movements, but he quickly became the target of a smear campaign by the nation’s white elite that opposed calls to change it racist views – at least publicly – in the years following World War II.

In this case, the person whose life has been uncovered more in depth is Raymundo Souza Dantas (1923-2002), a writer from Brazil’s northeast. A man of humble origins, he became first black man chosen to be an ambassador in the country’s diplomatic ranks, even as his presence was opposed by a racist, white elite.

Dantas (1923-2002) was named Brazil’s ambassador to Ghana by then-President Jânio Quadros in 1961. His appointment at the time was greeted positively by progressive movements, but he quickly became the target of a smear campaign by the nation’s white elite that opposed calls to change it racist views – at least publicly – in the years following World War II.

‘’In 1961, the Brazilian elite could no longer say openly what the problem was with the nomination of Raymundo to a post historically reserved for the cream of society,’’ revealed Koifman. ‘’Since it was wrong to say that he would not serve as ambassador because he was black, the argument adopted was that he was nobody, he had no expression as an intellectual, journalist, or writer, which is also not true.’’

Raymundo Souza Dantas was born in 1923 in the little town of Estância, Sergipe, 41 miles from Aracaju, the capital city. He taught himself to read and write in the back of a typography shop where he was employed in Rio.

Between the mid-1940s and the early 1960s, he had already developed a name for himself in Rio de Janeiro’s press, due to his work in a number of publications, including the magazine O Cruzeiro, and the newspaper Diário Carioca.

In the book, Koifman provides evidence that of Souza Dantas’ reputation, revisiting a 1946 issue of the A manha newspaper in which important and promising authors were mentioned, including Souza Dantas, whose name appeared alongside a teenage Clarice Lispector and Antonio Candido, who would later become known as one of Brazil’s best literary critics.

‘’Souza Dantas was named ambassador in the same wave as writer Rubem Braga and painter Cícero Dias, both also outside the diplomatic career. But none of them was so heavily criticized as Raymundo, who was black, poor and from an unknown northeastern family, everything that the elites, especially those from Rio de Janeiro, had a horror of,’’ says Koifman.

Apart from the obvious criticism that Souza Dantas faced, particularly from those connected to the Instituto Rio Branco, which was founded in 1945 to train professional diplomats, according to the author, many myths were fabricated about him.

Perhaps the most outlandish of these was the idea the Ghanaian government took so long to approve the Brazilian because Accra was irritated by the selection of a black man to head the Brazilian embassy in the country, in a Ghana which was formed in 1957 after independence from British rule. As Nkrumah is considered a major advocate of Pan-Africanism, it’s seems ridiculous that such an absurd idea was seriously accepted by anyone in the know.

‘’During my research, I found that historiography incorporated myths and rumors that circulated at the time and were repeated as truths,’’ says Koifman. ‘’In the case of the agrément, the approval of all nominees from outside the career was slow. Rubem Braga’s, for example, arrived much later than Raymundo’s, and Cícero Dias’ didn’t even arrive, so much so that he ended up not even going to Senegal.’’ Braga was a writer while Dias was a painter and illustrator.

Another fabrication story, according to Koifman, was that Ghana’s president and Pan-African political leader Kwame Nkrumah refused to meet with Souza Dantas for three months, and that after he agreed to meet with him, he mistreated him because he expected the same treatment as European embassies, where white diplomats were directed.

‘’This is one of the great lies that were invented against him. Raymundo’s official reception in Ghana took only eight days, and photos reveal that he even danced with Nkrumah, an honor accorded to few in the local culture. Queen Elizabeth II danced with Nkrumah!’’, said Koifman. ‘’The truth is that the Brazilian elite put their own prejudices into the mouths of others.’’

Souza Dantas’ mission to Ghana, which never gained adequate support – not because he was black, but because it was in Africa, as Koifman points out – ended when Jânio Quadros resigned in August 1961. His return to Brazil would happen in July of 1963, following a period of severe financial constraints that forced the embassy to cut back on staff and postpone salaries.

The Rio Branco Institute is the graduate school of International Relations and diplomatic academy located in Brazil’s capital city of Brasília. In 2002, coincidentally, the same year that Souza Dantas died, it launched the Affirmative Action Program (PAA) as a pioneering initiative to diversify the Brazilian civil service by awarding scholarships to blacks interested in pursuing diplomatic careers. In 2014, Law 12.990 was added to this program, ensuring that at least 20% of individuals selected in public competitions would be black.

Little progress

Today, 60 years after the Souza Dantas’ appointment, the situation in Brazilian diplomacy has remained largely unchanged, with just a small number of people ascending and managing to reach the top of the professional ladder.

The Ministry of Foreign Relations reports that it doesn’t know the exact number of black personnel because there are no documents that requests information about race or skin color. Such omissions have been challenged in recent years as Afro-Brazilian activists have demanded that this information about political figures be made available. According to Koifman’s research, just one other black person has risen to the rank of Minister of First Class, the highest post in diplomacy and the equal to that of an ambassador.

According to Ministry’s own information, 20 PAA scholarship recipients attended the Rio Branco Institute between the years of 2002 and 2014. Then, between 2014 and 2020, 32 black candidates were approved in the competition for admission to pursue a Diplomatic Career, with 27 of them being in openings reserved by Law 12.990 and only five in posts open to all. All told, the numbers show the rarity of black Brazilians in this area, indicating that only 5.4 percent of the 950 vacancies between 2002 and 2020 were filled by people identifying themselves as black.

In his book, Koifman comes to the following conclusion: “The precedent was established, by leaps and bounds and at the cost of much suffering for Raymundo. But the fact that so few Afro-Brazilians have reached the highest position in Itamaraty in the entire history of Brazil is more than enough evidence that resistance has existed and continues to exist, and that Brazilian society still has a long way to go before it can be considered or one day come close to the much-mentioned ‘racial democracy'”.